Notre Dame political and computer scientists probe authoritarian regimes’ use of social media to attack democracy

Russia’s pervasive use of online propaganda and disinformation seeks to sow distrust in elections, trigger violence, and destabilize populations around the world, said University of Notre Dame political scientist Karrie Koesel.

Unsuspecting citizens — in the United States and other democratic countries — may not even recognize that they're under attack.

“Authoritarian regimes — like Russia, China, and Iran — are actively using social media platforms to spread misinformation, and this has real-world impacts,” she said.

To better understand and be able to combat such online campaigns, Koesel and an interdisciplinary research team were selected to take part in a Defense Education and Civilian University Research (DECUR) Partnership, which is part of the Department of Defense’s research arm, the Minerva Research Initiative.

A goal, Koesel said, is to understand how people and social communities are manipulated, compromised, and converted in online spaces.

“To protect democracy at home and abroad, we must understand the different ways it is being attacked,” said Koesel, an associate professor of political science and a fellow of the Nanovic Institute of European Studies, the Kellogg Institute of International Studies, the Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies, the Pulte Institute for Global Development, and the Institute for Educational Initiatives.

Online propaganda campaigns take various forms, she said, from spreading disinformation about the validity of U.S. elections to misrepresenting the amount of support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

William Thiesen, an assistant teaching professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, found that in the days leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the number of Russian-backed activists’ posts increased by nearly 9,000% on a popular social media platform in Russia and Eastern Europe.

Related research, Koesel said, found that the Kremlin’s escalation of propaganda during that time frame significantly increased support for Russian military aggression against Ukraine.

“This helps us identify ways in which democracies are vulnerable,” she said, “and creates a pipeline from universities to policymakers so that our research has real-world impact.”

‘A picture is worth a thousand lies’

The research team, which has expertise in computational science, Russian studies, and linguistics, will identify and examine the origin, timing, techniques, and narratives of Kremlin propaganda leading up to and following the invasion of Ukraine.

The team also will conduct a case study to learn about the effects of propaganda on Russian speakers in Hungary and explore how to better forecast and mitigate the spread of false, dangerous narratives.

Hungary is an important case, Koesel said, because Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has demonstrated open support for Russia and Vladimir Putin.

“We've seen the blocking of aid to Ukraine, blocking new NATO members, and allowing Russian oligarchs to have financial dealings within Hungary,” she said. “Although Hungary is part of the European Union, it is a very pro-Russian space. Our research investigates how Kremlin narratives resonate in Russian-speaking communities there.”

The research team includes Notre Dame graduate students, as well as Tim Weninger, the Frank M. Freimann Collegiate Professor of Engineering, a leading expert on misinformation, particularly visual forms of misinformation.

“Tim brings a methodological skillset — what computer scientists often call digital forensics — to help us understand misinformation and propaganda online,” Koesel said.

Weninger has developed AI tools to sift through millions of social media images on Facebook, Instagram, X, YouTube, Telegram, and VKontakte and to identify those images that have been similarly manipulated and have the same narrative.

“We’re seeing coordinated campaigns of content," said Weninger, who is also an affiliate with the Lucy Family Institute for Data and Society, the Pulte Institute for Global Development, and the Technology Ethics Center. “If someone is trying to influence or manipulate how storytelling happens, then they can manipulate society. There’s nothing more important.”

Weninger advised social media users to be aware of their intellectual and emotional reactions to posts.

“Social media posts are meant to make you feel certain ways; they're not solely informational,” he said. “Recognize what a post or image or video is making you feel and think about how you're thinking about it. It’s called metacognition, and it’s important for understanding social media.”

The public will be able to read the findings from their project, “Kremlin Influence Operations in Online Spaces,” after it’s completed in 2026.

Koesel said this project — the first from Notre Dame to receive funding from the Minerva Research Initiative — aligns closely with the recently launched Notre Dame Democracy Initiative, an interdisciplinary research, education, and policy effort to advance solutions to sustain and strengthen global democracy.

Weninger said Notre Dame is built for this kind of research.

“It has collaborations between political scientists and computer scientists, and it has real-world impact,” he said. “This speaks to the very ethos of the place.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on June 13, 2024.

Latest Research

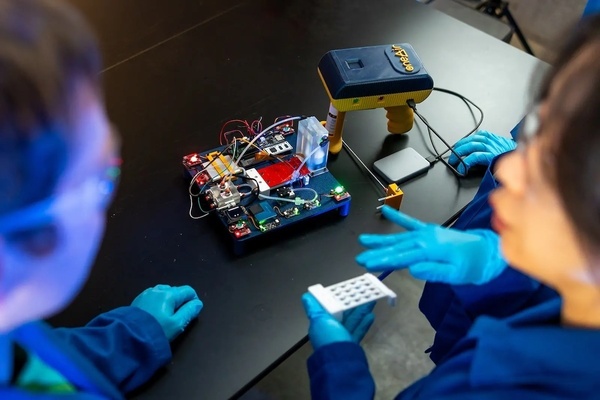

- Fighting for Better Virus DetectionAn electronic nose developed by Notre Dame researchers is helping sniff out bird flu biomarkers for faster detection and fewer sick birds. Read the story

- Notre Dame’s seventh edition of Race to Revenue culminates in Demo Day, a celebration of student and alumni entrepreneurship…

- Managing director brings interdisciplinary background to Bioengineering & Life Sciences InitiativeThis story is part of a series of features highlighting the managing directors of the University's strategic initiatives. The managing directors are key (senior) staff members who work directly with the…

- Monsoon mechanics: civil engineers look for answers in the Bay of BengalOff the southwestern coast of India, a pool of unusually warm water forms, reaching 100 feet below the surface. Soon after, the air above begins to churn, triggering the summer monsoon season with its life-giving yet sometimes catastrophic rains. To better understand the link between the formation of the warm pool and the monsoon’s onset, five members of the University of Notre Dame’s Environmental Fluid Mechanics Laboratory set sail into the Bay of Bengal aboard the Thomas G. Thompson, a 274-foot vessel for oceanographic research.

- Exoneration Justice Clinic Victory: Jason Hubbell’s 1999 Murder Conviction Is VacatedThis past Friday, September 12, Bartholomew County Circuit Court Judge Kelly S. Benjamin entered an order vacating Exoneration Justice Clinic (EJC) client Jason Hubbell’s 1999 convictions for murder and criminal confinement based on the State of Indiana’s withholding of material exculpatory evidence implicating another man in the murder.

- Notre Dame to host summit on AI, faith and human flourishing, introducing new DELTA frameworkThe Institute for Ethics and the Common Good and the Notre Dame Ethics Initiative will host the Notre Dame Summit on AI, Faith and Human Flourishing on the University’s campus from Monday, Sept. 22 through Thursday, Sept. 25. This event will draw together a dynamic, ecumenical group of educators, faith leaders, technologists, journalists, policymakers and young people who believe in the enduring relevance of Christian ethical thought in a world of powerful AI.