“Contagious capitalism”: Keough School Dean Mary Gallagher shares research insights on law, labor and justice in China

Mary Gallagher, the Marilyn Keough Dean of the Keough School of Global Affairs, delivered the fifth annual Justice and Asia Distinguished Lecture at the school’s Liu Institute for Asia and Asia Studies on April 8, drawing on her research expertise to share insights on law, labor and justice in China.

Gallagher, a political scientist and top scholar of contemporary China, explained how China has in recent decades employed state-controlled capitalism and the expansion of workers’ rights as tools to accelerate development. However, she said, this expansion of rights, in the context of weak enforcement by local governments, led to unmet expectations and social unrest. Gallagher also explained how Xi Jinping, who took office at the height of these protests, responded to threats of social instability by embracing a more authoritarian approach that seeks to strengthen China in an era of global competition.

Her talk, “Contagious Capitalism Revisited: Labor, Law and Justice in China” drew from her extensive China research, including her 2005 book “Contagious Capitalism: Globalization and the Politics of Labor in China” and her 2017 book, “Authoritarian Legality: Law, Workers and the State in China.”

“I argued that China went through these very difficult socialist reforms of socialism, like all socialist countries did,” said Gallagher, whose award-winning research explores Chinese domestic politics, political economy and industrial relations. “But it did so really late. And foreign companies came in during the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, and, in a significant way, supplied important parts of China’s growth story. They provided a regulatory framework. They provided human resources skills. They taught companies how to discipline workers. And this is the idea of contagious capitalism: They inserted capitalism into a socialist country.”

China’s government relied on a system of decentralized authoritarianism to facilitate regional competition and economic growth, Gallagher said. In addition, the government reduced resistance to neoliberal reforms by framing them not as ideological shifts, but as pragmatic adjustments that served the national interest.

Drawing on her 2017 book, Gallagher explored how China eventually sought to respond to its earlier success in shifting to a more capitalist economy. By the first decade of this century, China’s leaders were concerned about widening inequality, weak enforcement of labor and environmental regulations and growing social dissatisfaction with these programs. China sought to develop a system of good governance that didn’t lead to democracy.

Authoritarian legality relied on a rights-giving central state that decentralized enforcement and implementation to local government. The central government took credit for good laws, local government accepted blame for poor enforcement and the result, Gallagher said, was stronger trust in the central government.

As China rapidly urbanized, workers exchanged land security for employment security, Gallagher said, and labor contracts and social insurance became increasingly popular. Although the workplace saw improvements, political restrictions on freedom of association and the challenges workers faced in defending their rights through the courts limited the effectiveness of these changes.

“The expansion of labor rights was a tactical move, part of a larger strategy to change China’s development model, not an end in itself,” Gallagher said.

Although the Chinese government hoped that these gestures would tamp down dissent and protest, over time they had the opposite effect, leading to what Gallagher described as a cycle of law, instability and repression. Between 2011 and 2017, strikes and demonstrations increased massively in response to labor issues.

“Fear of social transformation and unrest led to a focus on preserving stability,” Gallagher said. “This included the repression of social movements and activities and the end of state’s legislative activism, and, largely, an end to redistributive reforms.”

Under Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party’s focus on “common prosperity” has increasingly meant state control, a crackdown on private capital and a development model that has shifted from consumption to an emphasis on manufacturing prowess, Gallagher said.

Today, Gallagher said, a “contagious authoritarianism” affects both China and the United States. Increasingly, she said, economic nationalism shapes how the two countries approach each other, and strongman leaders have retained significant domestic support. In addition, she said, U.S. policymakers have copied aspects of China’s approach, from industrial policy to patriotic education and the politicization of the judiciary.

“I don't think it's a complete coincidence that at a moment of high uncertainty and deep inequality, we see strongman leaders in both countries who use economic nationalism to attempt to unify their populations against the other,” she said.

About the Justice in Asia Lecture Series

The Justice and Asia Distinguished Lecture Series invites top scholars who examine the theme of justice in relation to Asia and with awareness of Asian cultures and traditions. The series is part of the Liu Institute’s organizing theme of “Justice and Asia” that examines and supports thematic work from a range of perspectives, projects, disciplines, and collaborations.

About the Liu Institute

The Keough School’s Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies, provides a forum for integrated and multidisciplinary research and teaching on Asia and its diaspora. The institute:

- Supports innovative projects that actively combine teaching, research and social engagement, creating a unique model of rounded education on Asia.

- Promotes general awareness, understanding and knowledge of Asia and its diaspora through organizing public events and supporting student and faculty scholarship and engagement with partners in Asia.

Originally published by at keough.nd.edu on April 24, 2025.

Latest Research

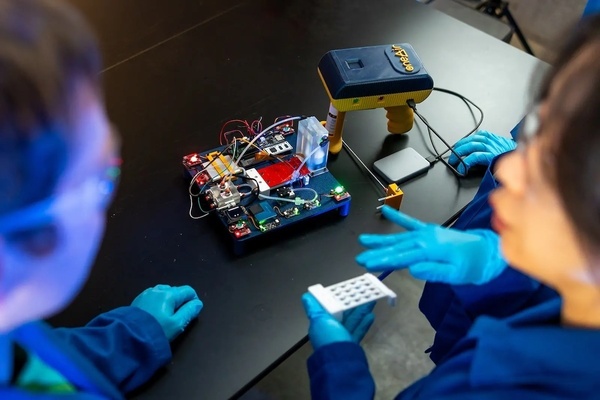

- Fighting for Better Virus DetectionAn electronic nose developed by Notre Dame researchers is helping sniff out bird flu biomarkers for faster detection and fewer sick birds. Read the story

- Notre Dame’s seventh edition of Race to Revenue culminates in Demo Day, a celebration of student and alumni entrepreneurship…

- Managing director brings interdisciplinary background to Bioengineering & Life Sciences InitiativeThis story is part of a series of features highlighting the managing directors of the University's strategic initiatives. The managing directors are key (senior) staff members who work directly with the…

- Monsoon mechanics: civil engineers look for answers in the Bay of BengalOff the southwestern coast of India, a pool of unusually warm water forms, reaching 100 feet below the surface. Soon after, the air above begins to churn, triggering the summer monsoon season with its life-giving yet sometimes catastrophic rains. To better understand the link between the formation of the warm pool and the monsoon’s onset, five members of the University of Notre Dame’s Environmental Fluid Mechanics Laboratory set sail into the Bay of Bengal aboard the Thomas G. Thompson, a 274-foot vessel for oceanographic research.

- Exoneration Justice Clinic Victory: Jason Hubbell’s 1999 Murder Conviction Is VacatedThis past Friday, September 12, Bartholomew County Circuit Court Judge Kelly S. Benjamin entered an order vacating Exoneration Justice Clinic (EJC) client Jason Hubbell’s 1999 convictions for murder and criminal confinement based on the State of Indiana’s withholding of material exculpatory evidence implicating another man in the murder.

- Notre Dame to host summit on AI, faith and human flourishing, introducing new DELTA frameworkThe Institute for Ethics and the Common Good and the Notre Dame Ethics Initiative will host the Notre Dame Summit on AI, Faith and Human Flourishing on the University’s campus from Monday, Sept. 22 through Thursday, Sept. 25. This event will draw together a dynamic, ecumenical group of educators, faith leaders, technologists, journalists, policymakers and young people who believe in the enduring relevance of Christian ethical thought in a world of powerful AI.