In sub-Saharan Africa, 1 in 6 cancer medications found to be defective

Serious quality defects were found in a significant number of cancer medications from sub-Saharan Africa, according to new research from the University of Notre Dame.

For the study published in The Lancet Global Health, researchers collected different cancer medications from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya and Malawi and evaluated whether each drug met regulatory standards. Researchers considered a variety of factors, including appearance, packaging, labeling and, most importantly, the assay value.

The assay value is the quantity of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) found in each drug. To meet safety standards, most products should be within a range of 90 to 110 percent of the right amount of API. Researchers measured the API content of each product and compared that number to what was designated on the medication packaging.

“It is important that cancer medications contain the right amount of the active ingredients so the patient gets the correct dose,” said Marya Lieberman, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Notre Dame and lead author of the study. “If the patient’s dose is too small, the cancer can survive and spread to other locations. If the patient’s dose is too high, they can be harmed by toxic side effects from the medicine.”

One in six cancer medications tested was found to contain the incorrect quantity of API, with tested medications having APIs ranging from 28 to 120 percent. The study evaluated 251 samples of cancer medications collected from major hospitals and private markets in all four countries.

The study, funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, is among the first to evaluate cancer drug quality in sub-Saharan Africa. Currently, sub-Saharan Africa has no pharmaceutical regulatory laboratories carrying out chemical analyses for cancer drugs according to the standards required for regulatory purposes.

Yet, the need for cancer drugs is growing.

“We found bad-quality cancer medications in all of the countries, in all of the hospital pharmacies and in the private markets,” said Lieberman, an affiliate of Notre Dame’s Eck Institute for Global Health and Harper Cancer Research Institute. “We learned that visual inspection, which is the main method for detecting bad-quality cancer drugs in sub-Saharan Africa today, only found one in 10 of the bad products.”

In their study, the researchers explained how a combination of high demand for cancer medications, lack of regulatory capacity, and poor manufacturing, distribution and storage practices likely created a problematic environment throughout sub-Saharan Africa. They also argue that given these factors and the global supply chain for pharmaceuticals, substandard cancer medications are likely present in other low and middle-income countries as well.

Lieberman and her team identified several strategies that could help the global community address poor-quality cancer medications:

- Provide inexpensive technologies at the point of care to screen for bad-quality cancer medicines and create policies for how to respond to products that fail screening tests.

- Help regulatory agencies in low and middle-income countries get safety equipment and training so they can analyze the quality of cancer medicines in their markets, conduct root-cause investigations when products fail testing, take quick regulatory actions enabled by lab data and share data about bad-quality products.

- Perform cost-benefit analyses of interventions that tackle common problems (such as medications being out of stock, unsafe shipping, storage or dispensing practices, and lack of availability or affordability of medications) to help policymakers and funders get the most impact on patient outcomes from their available resources.

- Work with care providers to develop site-specific response policies and messaging for patients and engage regulators, donors and other resources.

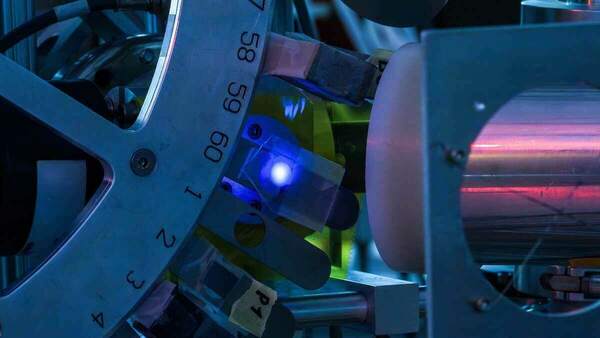

Lieberman and her lab are developing a user-friendly technology called the chemoPAD for screening cancer medications. This low-cost paper device could potentially help hospitals, pharmacies and health care professionals in low and middle-income countries monitor drug quality without restricting a patient’s access to the medication.

“This is all part of a bigger project aimed at developing the ChemoPAD as a point-of-care testing device that we can use, something that’s more accurate in detecting poor-quality products than just visual inspection,” Lieberman said.

“There are lots of medicines where the regulators don’t have enough resources to verify the quality, and some manufacturers take advantage of that to cut corners. There are also problems with distribution systems, so even if a product is good quality when it leaves the manufacturer, it may be degraded during shipping or storage. These products flow into low and middle-income countries, and they get used on patients. I want to change that.”

In addition to Lieberman, co-authors include Maximilian J. Wilfinger, Jack Doohan and Ekezie Okorigwe from Notre Dame; Ayenew Ashenef and Atalay Mulu Fentie from Addis Ababa University; Ibrahim Chikowe from Kamuzu University of Health Sciences; Hanna S. Kumwenda from the University of North Carolina Project Malawi; Paul Ndom from University of Yaoundé; Yauba Saidu from the Clinton Health Access Initiative; Jesse Opakas from the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital; Phelix Makoto Were from AMPATH - Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital; and Sachiko Ozawa and Benyam Muluneh from the University of North Carolina.

Contact: Brandi Wampler, associate director of media relations, 574-631-2632, brandiwampler@nd.edu

Originally published by at news.nd.edu on June 25, 2025.

Latest Research

- First impressions count: How babies are talked about during ultrasounds impacts parent perceptions, caregiving relationshipPsychologist Kaylin Hill studied the impact of a parent’s first impression of their baby during an ultrasound exam. The words used by the medical professional to describe the baby (positive or negative) influence how the parents perceive their baby, relate to them after they're born and even how that child behaves as a toddler. The research has broad implications for how we train medical professionals to interact with expectant parents, as well as how we care for parents during the perinatal period when they are most susceptible to depression.

- Researchers at Notre Dame detect ‘forever chemicals’ in reusable feminine hygiene productsWhen a reporter with the Sierra Club magazine asked Graham Peaslee, a physicist at the University of Notre Dame, to test several different samples of unused menstrual underwear for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in 2019, the results fueled concern over chemical exposure in feminine hygiene products — which ultimately ended up in a $5 million lawsuit against the period and incontinence underwear brand Thinx. Then in 2023, the New York Times asked Peaslee to test 44 additional period and incontinence products for PFAS, a class of toxic fluorinated compounds inherently repellent to oil, water, soil and stains, and known as “forever chemicals” for their exceptionally strong chemical and thermal stability. Measurable PFAS were found in some layers of many of the products tested — some low enough to suggest the chemicals may have transferred off packaging materials, while others contained higher concentrations, suggesting the chemicals were intentionally used during the manufacturing process. In the meantime, another group of researchers published a study that found PFAS in single-use period products, leading Peaslee and his lab to widen their investigation into all sorts of reusable feminine hygiene products — often viewed as an eco-friendly option by consumers. Now, the results of that study have been published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

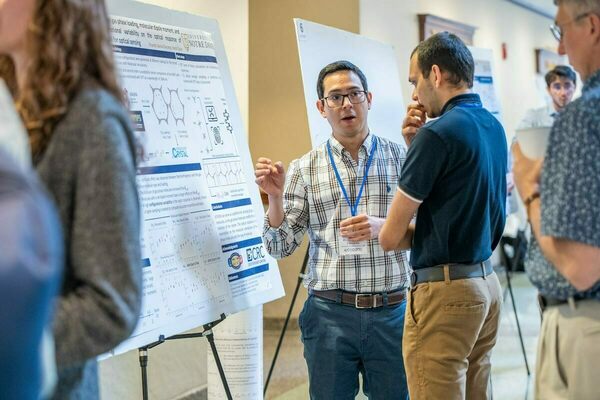

- Notre Dame hosts major international artificial intelligence and machine learning conferenceExperts from 22 different institutions of education and research located in 7 different countries gathered at the University of Notre Dame (South Bend, Indiana, USA) last week for a flagship workshop of the Centre Européen de Calcul Atomique et Moléculaire (CECAM).…

- University of Notre Dame and IBM Research build tools for AI governanceMain Building (Photo by Matt Cashore/University of Notre Dame) …

- Smarter tools for policymakers: Notre Dame researchers target urban carbon emissions, building by buildingCarbon emissions continue to increase at record levels, fueling climate instability and worsening air quality conditions for billions in cities worldwide. Yet despite global commitments to carbon neutrality, urban policymakers still struggle to implement effective mitigation strategies at the city scale. Now, researchers at Notre Dame’s School of Architecture, the College of Engineering and the Lucy Family Institute for Data & Society are working to reduce carbon emissions through advanced simulations and a novel artificial intelligence-driven tool, EcoSphere.

- Seven engineering faculty named collegiate professorsSeven faculty members in the Notre Dame College of Engineering have been named collegiate professors—a prestigious title awarded by the university and college in recognition of excellence in research, teaching and service. The designation may be conferred on faculty at the assistant, associate or…