Women of African ancestry may be biologically predisposed to early onset or aggressive breast cancers

While the incidence of breast cancer is highest for white women, Black women are more likely to have early-onset or more aggressive subtypes of breast cancer, such as triple-negative breast cancer. Among women under 50, the disparity is even greater: young Black women have double the mortality rate of young white women.

Now research from the University of Notre Dame is shedding light on biological factors that may play a role in this disparity. The study published in iScience found that a population of cells in breast tissues, dubbed PZP cells, send cues that prompt behavioral changes that could promote breast cancer growth.

Funded by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, the study set out to explore what biological differences in breast tissue could be related to early onset or aggressive breast cancers. Most breast cancers are carcinomas, or a type of cancer that develops from epithelial cells. In healthy tissue, epithelial cells form linings in the body and typically have strong adhesive properties and do not move.

The researchers focused on PZP cells as previous studies had shown that these cells are naturally and significantly higher in healthy breast tissues of women of African ancestry than in healthy breast tissues of women of European ancestry. While PZP cell levels are known to be elevated in breast cancer patients in general, their higher numbers in healthy, African ancestry tissues could hold clues to why early-onset or aggressive breast cancers are more likely to occur in Black women.

“The disparity in breast cancer mortality rates, particularly among women of African descent, is multifaceted. While socioeconomic factors and delayed diagnosis may be contributing factors, substantial emerging evidence suggests that biological and genetic differences between racial groups can also play a role,” said Crislyn D'Souza-Schorey, the Morris Pollard Professor of Biological Sciences at Notre Dame and corresponding author of the study.

The study showed how PZP cells produce factors that activate epithelial cells to become invasive, where they detach from their primary site and invade the surrounding tissue.

For example, a particular biological signaling protein known as AKT is often overactive in breast cancers. This study showed that PZP cells can activate the AKT protein in breast epithelial cells, which in part allows them to invade the surrounding environment. PZP cells also secrete and deposit certain proteins outside the cell that guide the movement of breast epithelial cells as they invade.

Overall, the results of the study emphasize multiple mechanisms by which PZP cells may influence the early stages of breast cancer progression and their potential contribution to disease burden.

The researchers also looked at how a targeted breast cancer drug, capivasertib, which inhibits the AKT protein, impacted PZP cells and found it markedly reduced the effects of the PZP cells on breast epithelial cells.

“It’s important to understand the biological and genetic differences within normal tissue as well as tumors among racial groups, as these variations could potentially influence treatment options and survival rates. And consequently, in planning biomarker studies, cancer screenings or clinical trials, inclusivity is important,” said D'Souza-Schorey, also an affiliate of Notre Dame’s Berthiaume Institute for Precision Health and Harper Cancer Research Institute.

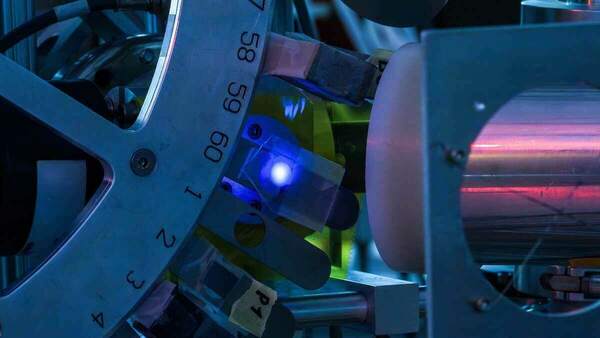

D'Souza-Schorey and her lab collaborated with the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Susan G. Komen Tissue Bank to access PZP cells and epithelial cells isolated from healthy breast tissues of both African and European ancestry. The cell lines were then grown in a three-dimensional environment, mimicking the way the cells would behave in living tissues and organs.

The research team also worked with the Notre Dame Integrated Imaging Facility for the study.

In addition to D’Souza-Schorey, co-authors include Madison Schmidtmann, Victoria Elliott, James W. Clancy, and Zachary Schafer from Notre Dame and Harikrishna Nakshatri from and IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Contact: Brandi Wampler, associate director of media relations, 574-631-2632, brandiwampler@nd.edu

Originally published by at news.nd.edu on July 24, 2025.

Latest Research

- Doctoral student Joryán Hernández to receive inaugural Sr. Dianna Ortiz, OSU Peacemaker AwardJoryán Hernández, a peace studies and theology doctoral student at the University of Notre Dame, was tapped as the first-ever recipient of the Sr. Dianna Ortiz, OSU Peacemaker Award from Pax…

- The Institute for Educational Initiatives at Notre Dame Launches Free Math App to Help Teachers Strengthen Students’ Understanding of Numbers and OperationsThe Number Sense Assessment app gives educators quick, research-based insights to target instruction and improve student outcomes Notre Dame, IN — Researchers at the Institute for Educational Initiatives at the University of Notre Dame have launched…

- U.S. Senator Todd Young on bridge-building in Congress and Notre Dame’s role in strengthening civil discourseThe University’s home state Senator discusses the importance of fostering common ground, on Capitol Hill and on campus

- Notre Dame researchers to shed light on the Brazilian Amazon, conflict resolution, microplastics, and moreNotre Dame Research (NDR) has selected five awardees of the Research and Scholarship Program – Regular Grant (RSP-RG) and five awardees of the Research…

- First impressions count: How babies are talked about during ultrasounds impacts parent perceptions, caregiving relationshipPsychologist Kaylin Hill studied the impact of a parent’s first impression of their baby during an ultrasound exam. The words used by the medical professional to describe the baby (positive or negative) influence how the parents perceive their baby, relate to them after they're born and even how that child behaves as a toddler. The research has broad implications for how we train medical professionals to interact with expectant parents, as well as how we care for parents during the perinatal period when they are most susceptible to depression.

- Researchers at Notre Dame detect ‘forever chemicals’ in reusable feminine hygiene productsWhen a reporter with the Sierra Club magazine asked Graham Peaslee, a physicist at the University of Notre Dame, to test several different samples of unused menstrual underwear for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in 2019, the results fueled concern over chemical exposure in feminine hygiene products — which ultimately ended up in a $5 million lawsuit against the period and incontinence underwear brand Thinx. Then in 2023, the New York Times asked Peaslee to test 44 additional period and incontinence products for PFAS, a class of toxic fluorinated compounds inherently repellent to oil, water, soil and stains, and known as “forever chemicals” for their exceptionally strong chemical and thermal stability. Measurable PFAS were found in some layers of many of the products tested — some low enough to suggest the chemicals may have transferred off packaging materials, while others contained higher concentrations, suggesting the chemicals were intentionally used during the manufacturing process. In the meantime, another group of researchers published a study that found PFAS in single-use period products, leading Peaslee and his lab to widen their investigation into all sorts of reusable feminine hygiene products — often viewed as an eco-friendly option by consumers. Now, the results of that study have been published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.