‘A special challenge’: German studies scholar wins National Humanities Center fellowship for research on medieval women

For CJ Jones, the joy of research is not the answers but the journey. And the next step on that journey is a fellowship with the National Humanities Center.

The NHC is a private nonprofit institute dedicated to the advanced study of the humanities, and Jones, a professor of German studies at the University of Notre Dame, has won a place in its 48th class of fellows.

Along with 31 humanitarian scholars, Jones will spend the coming academic year working on an individual research project that aims to bring to light women’s roles in religious history.

Fellows become resident scholars at the NHC’s idyllic, tree-ringed facility in North Carolina. While many organizations require fellows to prepare lectures or attend symposia, the NHC only asks that its scholars eat lunch together every day, taking a social approach to academic collaboration. That — plus the Center’s prestigious reputation and top-notch book request service — is why Jones is excited and grateful to pursue their research at the NHC.

Jones has published books, articles, and more on religious culture and literature in late medieval Germany with previous support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Their current academic interests center on the daily lives of those who are often overlooked in history — medieval women.

“People think we don’t have a lot of evidence about women because they were not very involved in producing culture in the Middle Ages, but increasingly, researchers have begun to demonstrate that this just isn’t true,” said Jones, who is the incoming Robert M. Conway Director of the Medieval Institute.

Though medieval women were not composing their own texts at the same rate men were, Jones said they had other ways of producing culture. Many rituals in medieval liturgy were designed for men, and when they were passed down, small but consequential restrictions placed on women — such as not being allowed to handle incense — were often not taken into account.

So women had to make their own adjustments, fitting together sometimes-competing sets of rules. Sources showing these adjustments — accounts by women and about their lives — are rarer in medieval studies, but for Jones, the disadvantage is more enticing than limiting.

“Women present a special challenge,” Jones said. “It’s this sort of exciting test, you know?”

Having previously studied medieval nuns through their diaries, Jones will take the research to the next level with their NHC project. Tentatively titled “Binding Ritual: Enclosed Women, Cultural Authority, and Liturgical Books in Late Medieval Germany,” Jones will examine the books women owned for signs of use and alteration.

“Are there patterns of wear? Are pages torn out?” Jones said. “Are there signs that something has been cleaned? Have they made notes in the margins? Has a book been taken apart and put back together again?”

Each manuscript requires a different kind of attention and skills to be understood, but Jones has experience in expanding boundaries to find answers about the past.

In January 2024, Jones traveled to Rome to take a class on codicology, the study of manuscripts as physical artifacts, and paleography, the study of ancient writing systems. They’ve returned to the Italian city for the summer, this time learning about hagiography, medieval writings on saints, and textual editing. Later in July 2025, Jones will also teach a course about monastic education in the Middle Ages and lead a conference on medieval religious women at Notre Dame Rome.

“The reason you get into this business is that you don’t want to stop learning,” Jones said. “Being a professor, you can just learn forever.”

Jones hopes the insights of the “Binding Rituals” project will increase appreciation for the amount of effort medieval women put into preparing religious services and following regulations that were designed largely by and for men.

While many today may not face the exact same issues, Jones said, they can still confront conflicts of tradition and individual community needs.

“Understanding history gives us hope in our own time,” Jones said, “to seize the agency to make our own better future.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on July 07, 2025.

Latest Research

- Notre Dame researchers to shed light on the Brazilian Amazon, conflict resolution, microplastics, and moreNotre Dame Research (NDR) has selected five awardees of the Research and Scholarship Program – Regular Grant (RSP-RG) and five awardees of the Research…

- First impressions count: How babies are talked about during ultrasounds impacts parent perceptions, caregiving relationshipPsychologist Kaylin Hill studied the impact of a parent’s first impression of their baby during an ultrasound exam. The words used by the medical professional to describe the baby (positive or negative) influence how the parents perceive their baby, relate to them after they're born and even how that child behaves as a toddler. The research has broad implications for how we train medical professionals to interact with expectant parents, as well as how we care for parents during the perinatal period when they are most susceptible to depression.

- Researchers at Notre Dame detect ‘forever chemicals’ in reusable feminine hygiene productsWhen a reporter with the Sierra Club magazine asked Graham Peaslee, a physicist at the University of Notre Dame, to test several different samples of unused menstrual underwear for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in 2019, the results fueled concern over chemical exposure in feminine hygiene products — which ultimately ended up in a $5 million lawsuit against the period and incontinence underwear brand Thinx. Then in 2023, the New York Times asked Peaslee to test 44 additional period and incontinence products for PFAS, a class of toxic fluorinated compounds inherently repellent to oil, water, soil and stains, and known as “forever chemicals” for their exceptionally strong chemical and thermal stability. Measurable PFAS were found in some layers of many of the products tested — some low enough to suggest the chemicals may have transferred off packaging materials, while others contained higher concentrations, suggesting the chemicals were intentionally used during the manufacturing process. In the meantime, another group of researchers published a study that found PFAS in single-use period products, leading Peaslee and his lab to widen their investigation into all sorts of reusable feminine hygiene products — often viewed as an eco-friendly option by consumers. Now, the results of that study have been published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

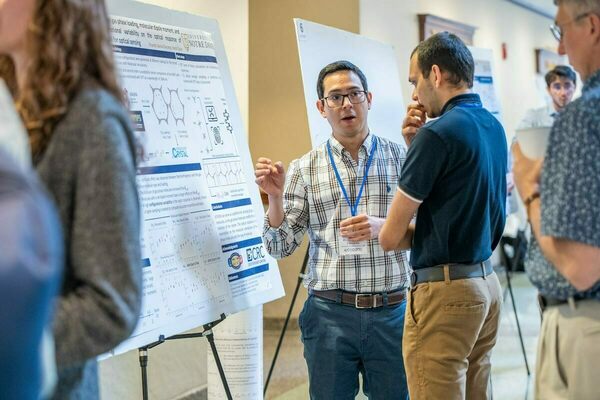

- Notre Dame hosts major international artificial intelligence and machine learning conferenceExperts from 22 different institutions of education and research located in 7 different countries gathered at the University of Notre Dame (South Bend, Indiana, USA) last week for a flagship workshop of the Centre Européen de Calcul Atomique et Moléculaire (CECAM).…

- University of Notre Dame and IBM Research build tools for AI governanceMain Building (Photo by Matt Cashore/University of Notre Dame) …

- Smarter tools for policymakers: Notre Dame researchers target urban carbon emissions, building by buildingCarbon emissions continue to increase at record levels, fueling climate instability and worsening air quality conditions for billions in cities worldwide. Yet despite global commitments to carbon neutrality, urban policymakers still struggle to implement effective mitigation strategies at the city scale. Now, researchers at Notre Dame’s School of Architecture, the College of Engineering and the Lucy Family Institute for Data & Society are working to reduce carbon emissions through advanced simulations and a novel artificial intelligence-driven tool, EcoSphere.