How can we have better conversations about environmental conservation? New Notre Dame research charts a path.

As the planet faces mounting environmental crises, including a decline in global biodiversity, a new study from the University of Notre Dame calls for a seemingly simple yet transformative practice: better conversations.

In a co-authored paper published in Conservation Biology, Daniel C. Miller outlines five key principles to foster more effective and inclusive dialogue about conservation. The paper builds on more than a decade of collaborative work in conservation social science and presents a framework to address one of the field’s most pressing yet underexamined issues—how conservationists talk to one another.

“We often talk past each other in conservation,” said Miller, the Coyle Mission Collegiate Associate Professor at Notre Dame’s Keough School of Global Affairs. “As the field has expanded, so has the diversity of voices and worldviews—bringing with it friction, misunderstandings and competing priorities. Yet conservation is a multidisciplinary effort, requiring insights from ecology, economics and other social sciences as well as engineering, law and humanities. We have to learn to talk to one another more effectively.”

Conservation is fundamentally about people and the choices they make, said Miller, a core faculty affiliate of the Keough School’s Pulte Institute for Global Development, yet despite growing recognition of this principle, social science perspectives are still marginalized in conservation science, education and policy. Many practitioners struggle with integrating diverse viewpoints—especially when disagreements emerge around values, methodologies, or the role of science in political decision-making.

Miller and co-authors Ivan R. Scales from the University of Cambridge and Michael B. Mascia of Duke University argue that embracing this pluralism is not a weakness, but a strength—if managed with intentional dialogue.

“We’re not calling for everyone to agree,” Miller said. “Disagreement can be productive. But we need a shared vocabulary and a mutual willingness to understand where others are coming from.”

The five principles

The heart of the paper lies in five guiding principles designed to make conservation conversations more constructive:

- Engage with plural perspectives – Accept that people view conservation through different lenses—whether they are scientists, Indigenous leaders, community organizers or policymakers. These views should not be caricatured or dismissed.

- Everyone does not need to agree on everything – The goal is not perfect consensus but rather a productive engagement with disagreement, recognizing that trade-offs are inevitable.

- Seek basic knowledge of different disciplines and ways of knowing – Conservationists should be “bilingually literate,” Miller said. “If you’re a social scientist, know a bit about biology. If you’re a biologist, learn some social science.”

- Science can inform but not determine decision-making – Policy is always political. Science can guide deliberation, but values, public opinion and context will also shape outcomes.

- Recognize and address unequal power relationships – This, Miller said, is the hardest but most important principle. “Power is entrenched. People don’t give it up easily. But unless we confront these inequalities, especially between the Global North and South, conservation efforts won’t be just—or effective.”

The paper also introduces a five-step framework for structuring conservation conversations, beginning with clarifying the purpose of the dialogue and ending with follow-up actions to ensure impact. Its content is rooted in insights gained during the development of “Conservation Social Science: Understanding People, Conserving Biodiversity,” a comprehensive textbook Miller co-edited with Scales and Mascia. The book and its discussions—spanning workshops from Brazil to Kenya—highlighted a shared frustration: conversations in the conservation world often fail to bridge key differences.

“Some contributors were anthropologists, some were economists, others were practitioners or activists,” said Miller. “It was clear we needed some ground rules—not to silence disagreements but to make them meaningful.”

Miller sees the principles as not just for academics or nongovernmental organizations but for all conservation stakeholders such as local landowners, multinational organizations and policymakers.

“We need these conversations to happen between researchers and practitioners, but also with people who live where conservation is taking place,” Miller said. “They have the most at stake and should help shape the outcomes.”

Miller said he believes the principle highlighting power disparities is the most important.

“Most people don't want to give up power,” he said. “But unless we shift who holds decision-making authority, especially in historically marginalized communities, we won’t achieve lasting conservation.”

Miller’s field work in the Global South often takes him to some of the world’s most disadvantaged communities, and he said this has shaped his thinking.

“I work with Indigenous peoples who are stewards of incredible biodiversity. We need ensure they—not outsiders—are determining what conservation looks like in their lands.”

Miller pointed to research showing that the best conversations happen not in abstract settings but in specific places—on a piece of land, in a local marine reserve—where people share a stake in the outcome. “Being in the place you’re talking about can lower the walls,” he said.

As societies become more politically polarized and communication grows increasingly adversarial, Miller believes better conversations are urgently needed—not just in conservation but in broader societal debates.

“We’re walled off from other views,” he said. “Our conversations are getting worse, not better. This paper is a small step toward rebuilding trust and opening space for real dialogue.”

The paper aligns closely with Notre Dame President Rev. Robert A. Dowd, C.S.C.'s vision of Notre Dame as a bridge-builder that fosters dialogue across differences, especially on difficult moral and political questions, Miller said.

“Better conversations won’t solve everything,” Miller said. “But they’re a necessary first step—to better research, better policy, and ultimately, better outcomes for both people and nature.”

Miller hopes the principles will become a touchstone for a more integrated, equitable and enduring approach to conservation.

“Conservation is not just about saving species,” he said. “It’s about the kind of world we want to live in—and who gets to decide.”

Foundational research for the paper was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Daniel Miller

Coyle Mission Collegiate Associate Professor

Dan Miller researches environmental politics and policy.

Full BiographyOriginally published by at keough.nd.edu on September 11, 2025.

Latest Research

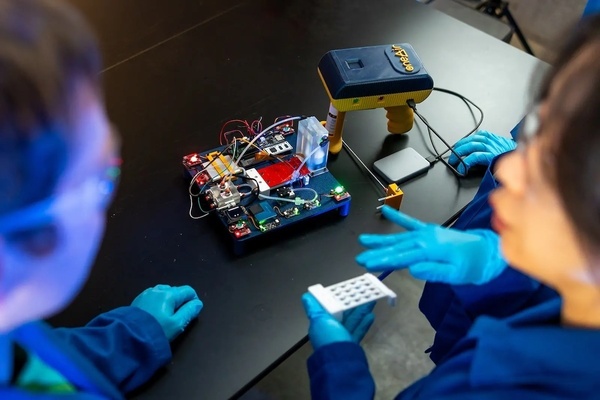

- Fighting for Better Virus DetectionAn electronic nose developed by Notre Dame researchers is helping sniff out bird flu biomarkers for faster detection and fewer sick birds. Read the story

- Notre Dame’s seventh edition of Race to Revenue culminates in Demo Day, a celebration of student and alumni entrepreneurship…

- Managing director brings interdisciplinary background to Bioengineering & Life Sciences InitiativeThis story is part of a series of features highlighting the managing directors of the University's strategic initiatives. The managing directors are key (senior) staff members who work directly with the…

- Monsoon mechanics: civil engineers look for answers in the Bay of BengalOff the southwestern coast of India, a pool of unusually warm water forms, reaching 100 feet below the surface. Soon after, the air above begins to churn, triggering the summer monsoon season with its life-giving yet sometimes catastrophic rains. To better understand the link between the formation of the warm pool and the monsoon’s onset, five members of the University of Notre Dame’s Environmental Fluid Mechanics Laboratory set sail into the Bay of Bengal aboard the Thomas G. Thompson, a 274-foot vessel for oceanographic research.

- Exoneration Justice Clinic Victory: Jason Hubbell’s 1999 Murder Conviction Is VacatedThis past Friday, September 12, Bartholomew County Circuit Court Judge Kelly S. Benjamin entered an order vacating Exoneration Justice Clinic (EJC) client Jason Hubbell’s 1999 convictions for murder and criminal confinement based on the State of Indiana’s withholding of material exculpatory evidence implicating another man in the murder.

- Notre Dame to host summit on AI, faith and human flourishing, introducing new DELTA frameworkThe Institute for Ethics and the Common Good and the Notre Dame Ethics Initiative will host the Notre Dame Summit on AI, Faith and Human Flourishing on the University’s campus from Monday, Sept. 22 through Thursday, Sept. 25. This event will draw together a dynamic, ecumenical group of educators, faith leaders, technologists, journalists, policymakers and young people who believe in the enduring relevance of Christian ethical thought in a world of powerful AI.