Family guy: Notre Dame anthropologist Lee Gettler broadens perspectives on fatherhood, raising healthy children

Lee Gettler can tell a lot about a man based on his spit.

It’s not about whether he does it on a baseball field, with watermelon seeds, or not at all. Gettler is much more interested in what’s inside it.

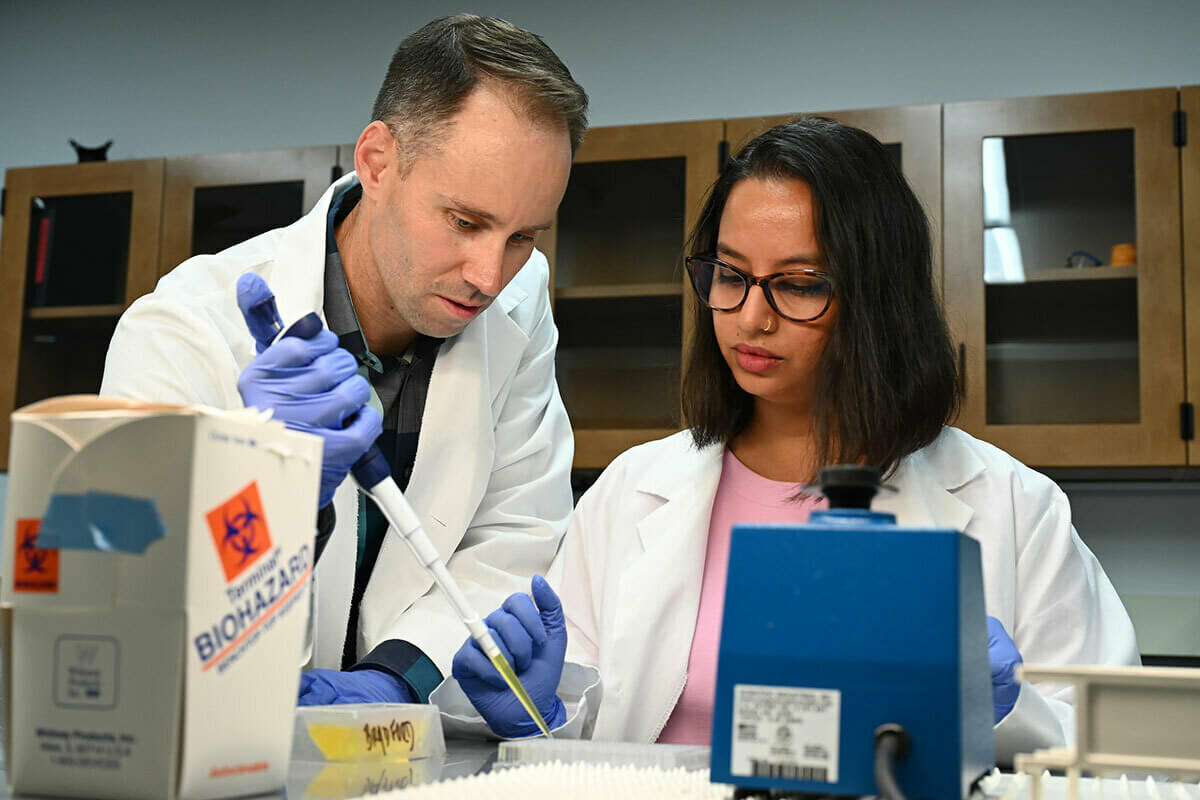

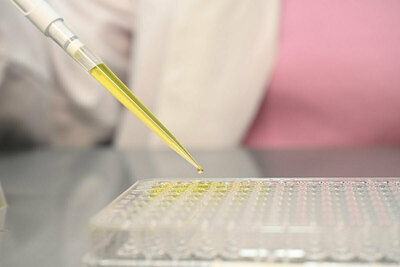

In his Hormones, Health, and Human Behavior Laboratory inside Corbett Family Hall, Gettler has freezers full of saliva samples (as well as fingernail clippings) from people from around the world. By studying the chemical composition of these specimens, the associate professor of anthropology has developed several groundbreaking studies that have focused attention on — and reframed perspectives about — fatherhood.

“For a long time, there have been questions in anthropology about how humans evolved to cooperate to raise children,” he said. “It’s important to think about where fathers fit into that cooperative network. Fathers have traditionally been thought of only as providers, and I have tried to expand that conversation.”

Gettler has focused on testosterone levels in men — in places as nearby as South Bend and locations as far away as the Philippines and the Republic of the Congo — and how those levels change (or don’t change) as they grow, age, and become fathers.

His goal is to examine and share the diverse ways that fathers and families around the world raise children, and to support the wide range of approaches to bringing up healthy youth.

“How children learn to parent and why they mimic or diverge from the care they received growing up are very important questions for how we can encourage healthy environments for children across generations,” Gettler said.

Testosterone tradeoffs

In his small hometown in Minnesota, Gettler and his childhood friends joked about how men — including their dads — seemed to get bigger as they aged and become stronger once they had children.

Back then, he hadn’t heard of anthropology — a multidimensional exploration of what it means to be human, past and present, nearby and distant. But now, Gettler is proving that he was onto something as an adolescent, just in a different sense than he and his friends intended.

“Important biological changes that men experience as parents are largely invisible to the naked eye,” he said, “but they’re visible in terms of the potential behaviors that come along with them.”

As an undergraduate at Notre Dame studying anthropology, Gettler ’05 was fascinated by the discipline. And when he learned that less than 5 percent of male mammals care for their young, he began wondering why human fathers were among the few who did.

“Important biological changes that men experience as parents are largely invisible to the naked eye, but they’re visible in terms of the potential behaviors that come along with them.”

That curiosity has led Gettler to make discoveries about fathers’ invisible development across the globe. What he’s found is an interesting paradox — as young adults, men with higher testosterone levels are more likely to find long-term partners, but later are more likely to be in marriages with strife. Men with lower testosterone levels when their babies are born are more involved caregivers and, in turn, the sons of involved dads have lower testosterone levels when they themselves become fathers.

Whether higher or lower testosterone levels — and behaviors and qualities associated with each — are valued depends on the culture in which the men live, Gettler has found, and can’t be deemed as good or bad, or better or worse. But understanding the impact that hormone levels can have on men and their families paints a more complete portrait of the complexities of fatherhood.

“Testosterone mediates tradeoffs between mating and parenting,” he said. “Men’s hormone physiology responds to major life transitions, including marriage and fatherhood, and men’s hormones relate to their behaviors as parents and partners.”

Spit takes

In order to better understand those complexities of fatherhood, Gettler needs physical samples — and lots of them.

Obtaining saliva from study participants is easy and noninvasive, Gettler said. People only have to spit — or take part in “passive drooling,” as it’s jokingly referred to — into small tubes. He then analyzes saliva samples that contain hormones — primarily cortisol and testosterone — in his lab.

Gettler and his team have collected plenty of such samples in Cebu, a metropolitan center of nearly 1 million people in the Philippines. While there, he met residents and learned about their culture when walking from his neighborhood to the university, and by joining in pickup basketball games. Working as part of a unique, longitudinal study that has tracked a large number of people in Cebu since birth, he also found evidence of the intergenerational effects of fathering, informed by 40 years’ worth of data.

Gettler and colleagues discovered that Filipino sons whose fathers were present and involved with raising them during adolescence had lower testosterone when they became fathers than did sons whose fathers were less involved or didn’t live with them during that stage.

There is still a lot to learn about how fathers shape their children’s potential as parents, he said, but the pieces are starting to come together.

“To me, this shows how parenting and fathering, particularly, can have lasting effects across generations, not just through behavior but also through biology,” said Gettler, who is also a faculty fellow of the Eck Institute for Global Health and the William J. Shaw Center for Children and Families. “But there has been even less research on the effect of fathers on children’s biology, which can directly impact their future health.”

Nurturing nature

That 2022 study, like many of his previous projects, received funding from the National Science Foundation. Gettler’s research has also been supported by the Wenner Gren Foundation, the Jacobs Foundation, and the Rukavina Family Foundation, among others. In the last five years alone, the researcher has participated in 39 peer-reviewed studies, including 14 as principal investigator/lead author. In 2020, in recognition of his substantial contributions to human biology, and the promise of future significant discoveries, the Human Biology Association presented Gettler with its Michael A. Little Early Career Award.

Twelve years ago, Gettler broke new ground with a study of 600 men in the Philippines that documented how men’s testosterone plummets during their 20s when they transition from being single and child-free to being coupled and having children.

After becoming fathers, the men experienced dramatic declines in testosterone (more than 25 percent on average); the declines were substantially greater than age-related declines of the single nonfathers. In that same longitudinal project — he also learned that single child-free men with high testosterone were more likely to become partnered fathers within 4.5 years than their counterparts with low testosterone.

Gettler also discovered that partnered fathers who spent time with their children for three or more hours a day had lower testosterone than fathers who didn’t care for their kids. The study, he said, demonstrated that the transition to fatherhood leads to big, meaningful changes in testosterone. Put another way, biology adjusts to fatherhood.

The findings drew considerable attention from the press, including the New York Times, Washington Post, Time, and NPR (it also caught the attention of late-night comedians — Stephen Colbert joked about the study on Twitter and Conan O’Brien referenced it in a monologue on his show).

A new study says fatherhood leads to a drop in testosterone. It's the kind of thing I used to get furious about before I had kids.

— Stephen Colbert (@StephenAtHome)September 13, 2011

During the media blitz, reporters sometimes asked Gettler if the results indicated that men were turning into women. What message, they asked, did he have for men worried that being an involved father was emasculating?

Gettler, himself an involved father of two who enjoys conversationally communicating his discoveries — in interviews and blogs, and on podcasts and Twitter (@LeeGettler) — had a succinct response: Testosterone doesn’t equal manliness.

Women also produce and utilize testosterone, which plays a role in cognitive health, bone mass, and the growth and health of reproductive tissues. In men, it regulates immune function, bone mass, fat distribution, muscle mass and strength, as well as the production of red blood cells and sperm.

His study was actually good news for men, he said, as it indicates the frequent portrayal of men as bumbling fools lacking the capacity to parent isn’t true. Men, like women, are biologically adapted to parenting.

“People conflate testosterone and masculinity and conflate one biological signal in human bodies with a very complex gender role that has many social expressions,” he said.

Humans were able to evolve the way they did because of the expansiveness of their brains, he said, which requires a long developmental period of 15 or more years. And because humans often had more than one child in close succession, considerable time and energy were needed to raise them.

Mothers, he said, needed a cooperating partner. Evolutionarily, fathers became an important part of that package.

“Testosterone is one of the key mechanisms that probably was pulled into this evolution of invested human fatherhood,” said Gettler. “We still see the biological signatures of that today in families in diverse settings around the world. We’re one of the few species that evolved to have dads engage in this kind of costly care.”

“People conflate testosterone and masculinity and conflate one biological signal in human bodies with a very complex gender role that has many social expressions.”

‘Shaped by the world’

Gettler gained additional insights about testosterone, men’s bodies, and dads engaged in costly care when he studied fathers of newborns in the childbirth center at Memorial Hospital in South Bend. He and his team collected hormone data from new dads in the first hour after their babies were born.

Men whose testosterone level was lower when their children were born were more involved months later as parents — changing diapers, playing, and doing household tasks related to the baby — than counterparts with higher testosterone levels.

And new dads also experienced a spike in oxytocin (a hormone associated with empathy, trust, and relationship-building) when they held their newborns for the first time. New fathers had the largest increase in oxytocin, while more experienced dads had higher overall oxytocin.

The hormone plays an important role in lactation and mother-infant bonding across mammals, but these findings show it is also primed to respond in dads’ bodies, from the earliest moments of parenting.

“For mothers, we see robust changes in their bodies going through pregnancy, birthing, and breastfeeding,” Gettler said. “It was long-assumed that men were along for the ride. Now, we know men’s bodies have other capacities to respond that facilitate their role in families.”

To better understand how culture impacts biology and fathering, Gettler also examined men’s testosterone levels in relation to their expected social roles in two communities in the Republic of the Congo.

“One of the things that I’m really interested in as an anthropologist is how culture pushes around these biological mechanisms and can really affect how they’re expressed,” he said. “We’re shaped by the world we operate in.”

That is evidenced by BaYaka and Bandongo men. While both societies value fathers as providers, the communities’ significant differences helped Gettler and collaborators tease out the role of culture.

Among the egalitarian BaYaka — where child care is shared and spousal conflict is frowned upon — men forage for food and share it with the community. Those considered by peers to be the best fathers/providers had lower testosterone than other men in the community.

And among the patriarchal, hierarchical Bandongo — where child care is less of a father’s responsibility — men fish and farm for food. Sometimes they engage in risky behavior to secure those resources. Men considered to be the best fathers/providers in this society had higher testosterone than their peers.

“One of the things that I’m really interested in as an anthropologist is how culture pushes around these biological mechanisms and can really affect how they’re expressed. We’re shaped by the world we operate in.”

“It’s important to understand that what it means to be a good dad is based on the way the culture values it,” Gettler said of the findings.

While men with lower testosterone in the BaYaka community were viewed as the best dads and men with higher testosterone in the Bandongo community were viewed as the best dads, men in both communities with higher testosterone had more marital conflict.

Higher testosterone is linked to physical attributes (greater muscle mass and strength) and social dynamics (competition, pursuit of status, and resources) that can attract mates. But testosterone-linked behaviors — competitiveness, dominance, lower empathy — can interfere with relationship stability.

“Indeed, men with higher testosterone have been shown to be more likely to have marital problems and to be divorced in the U.S. and elsewhere around the world,” he said, “and men with lower testosterone are described as more committed and supportive by their partners.”

Expanding the scope

Gettler’s research now also examines young people’s health. And, it turns out, he can also often tell how well a child’s parents get along based on the youth’s fingernails.

In BaYaka society, where there’s a strong cultural emphasis on cooperative caregiving, Gettler explored how family dynamics and marital discord correspond to children’s stress. He did so by comparing the level of cortisol — a stress hormone — in youth fingernails with men’s fulfillment of locally valued father roles.

He found that children with higher cortisol levels had parents in marriages with more conflict. They also had fathers who were less-effective providers and less generous when it came to sharing resources.

And in the patriarchal, hierarchical Bandongo society, children in families with more parental strife had greater intrinsic epigenetic age acceleration. That is, their biological “age” was older than their chronological age.

“We know that accelerated biological aging is strongly predictive of long-term mortality and risk of disease, which suggests family conflict has long-term implications for children's health and well-being,” he said.

Gettler is now working on a project, funded by the National Science Foundation, that builds on his prior research on the biology of family life in the Congo Basin. He’s exploring the role of adolescents as change-makers in communities where new jobs, technology, and trade practices are being introduced, and where economic and social transitions are occurring.

His research team also is examining how these social and economic transitions — that include experiences of inequality — shape how adolescents’ genes are expressed, and whether there are long-term health implications.

As communities in the United States also are undergoing significant economic and cultural shifts, Gettler said understanding the impacts those changes have on youth will be key to timely and effective interventions.

The amount of time that many fathers in the U.S. spend with their children has increased fairly dramatically in the last couple of decades. Simultaneously, he said, they’re still valued for their role as a provider.

Personally, Gettler said, having academic knowledge about fathering doesn’t always translate to personal expertise. Sometimes, he has second-guessed himself as a dad because of it. Being a father, though, has consistently informed his research interests.

“As a dad and co-parent, watching kids go through different phases has taught me a great deal about how to think about types of questions we might ask about fathers,” he said.

And, as it turns out, those humorous observations that he and his friends made as adolescents about fatherhood changing men were right.

But for the wrong reasons.

“Some things we were jokingly saying might cause changes in men, like carrying your babies around, actually have real, profound biological effects — just not the ones we were attributing to it,” he said.

“We were defining what might change men when they became fathers based on things we had experienced with our own dads. And those types of behavioral patterns are the ones that we have now tracked to these hormone shifts.”

“Some things we were jokingly saying might cause changes in men, like carrying your babies around, actually have real, profound biological effects — just not the ones we were attributing to it.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on March 22, 2023.

Latest Research

- Notre Dame celebrates 125 years of wireless innovation and educationThe University of Notre Dame is celebrating 125 years of wireless research, education and innovation with a modern re-enactment of one of the first long-range wireless transmissions conducted in the United States and a full-day symposium of panels and…

- Student Researcher Investigates PFAS AccumulationScat, something that most may not think much about — or even like dealing with — is, for Juan Flores, a fascinating look into animal behavior and aquatic chemistry. His research, with the guidance of Daniele Miranda, assistant research…

- Five Notre Dame faculty elected AAAS Fellows as program celebrates 150th anniversaryToday, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), one of the world’s largest general scientific societies and publisher of the Science family of journals, announced its newest class of AAAS Fellows, including five faculty from the University of Notre Dame. This class represents…

- Visit by Fr. Paolo Benanti, AI advisor to Pope Francis, deepens Notre Dame’s commitment to socially responsible data and AI innovationBest known for providing expert advice on machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) to Pope Francis, Fr. Paolo Benanti has a contagious enthusiasm for the ethics of technological advancement.…

- Subhash L. Shinde elected 2024 MRS Fellow…

- Notre Dame launches University-wide Democracy Initiative to advance research, education and policy efforts to sustain and enhance democracyThe University of Notre Dame has launched an ambitious new Democracy Initiative, an interdisciplinary research, education and policy effort focused on advancing solutions to sustain and strengthen global democracy.…